Here’s what deforestation looks like in 2019 – and what we can do about it

In 2018, the world lost about 30 million acres of forest, according to important new data from World Resources Institute. 30 million acres is about 47,000 square miles – that’s an area roughly the size of the state of New York, significantly larger than the state of Virginia, and larger than 31 of the 50 US states. This data should help guide conservation priorities as we work to save the world’s precious rainforests.

WRI’s analysis this year focuses mostly on ancient primary forests, those that house the most biodiversity and terrestrial carbon. It’s important to note, however, that primary forests aren’t the only ones that matter: secondary, or regenerating, forests comprise much of the world’s remaining forests, more than two-thirds in Asia, and even greater proportions in North and Central America. Many companies and governments have made commitments to protect those secondary forests too. And in many cases secondary forests are regenerating, restoring wildlife and carbon to the land. But protecting the Earth’s last remaining original forests remains the world’s top conservation priorityBrazil’s deforestation “success story” is in serious trouble[vc_separator sep_color=”color-205066″ icon_position=”left” el_width=”20%” el_height=”4″]Between 2004 and 2012, Brazil reduced deforestation in the Amazon by more than two-thirds, even as it started to regrow tens of millions of acres that had previously been destroyed. This success was achieved largely but not exclusively by private sector action: big animal feed traders like Louis Dreyfus, ADM, Bunge and Cargill banned deforestation for soy in the Brazilian Amazon, and within three years had virtually eliminated it. Interestingly, this “Soy Moratorium” was about five times as successful as any action by the Brazilian government. Big supermarkets and cattle slaughterhouses implemented similar policies; while not as comprehensive as soy, deforestation for cattle was dramatically reduced. Meanwhile, the Brazilian government protected millions of acres as indigenous reserves and protected areas.

Unfortunately, just as Brazil’s private sector was showing the world how to break the link between agriculture expansion and deforestation, a narrow segment of agribusiness interests in Brazil used their political influence to undermine this progress. In 2012, Brazil weakened aspects of its Forest Code, signaling greater toleration for deforestation even where it was legally prohibited. These weaker protections meant Brazilian ecosystems were doubly vulnerable, subject to both a changing climate and industrial exploitation. In 2016 and 2017, Brazil’s vast Cerrado ecosystem continued to be cleared for soy and cattle even as drier climate conditions led to record levels of primary forests burning in the Amazon.

The tragedy of this intentional deforestation was that it was entirely unnecessary. Brazil has tens of millions of acres of previously deforested lands where agriculture can be profitably expanded without threatening native vegetation. Brazil could remain a growing agricultural juggernaut without razing any forests.

The tragedy of this intentional deforestation was that it was entirely unnecessary. Brazil has tens of millions of acres of previously deforested lands where agriculture can be profitably expanded without threatening native vegetation. Brazil could remain a growing agricultural juggernaut without razing any forests.

Though conditions were wetter in 2018, which helped limit the risk of extensive forest fires, threats to forests have probably only increased with the election of President Jair Bolsonaro. Although Bolsonaro won mostly on promises to clean up corruption and stop crime, he has also formed an unholy alliance with anti-environment agribusiness interests and undermined protection of indigenous peoples.

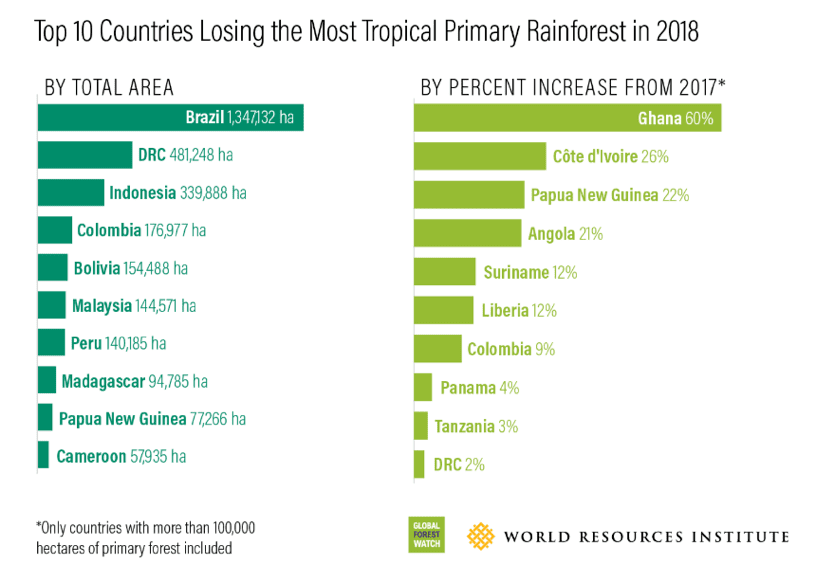

Given Bolsonaro’s hostility to environmental and indigenous protection, it falls to the private sector to drive action, as they did in the past with the Soy and Cattle Moratoria. There is an urgent need for companies like Ahold Delhaize, Sodexo, LDC, Bigard, Burger King, and McDonald’s to shift their supply chains. They should stop sourcing animal feed from companies that continue to engage in deforestation, like Bunge, and instead purchase from others like Louis Dreyfus Company and COFCO – companies that are taking action to protect forests and looking to expand the success of the Soy Moratorium. Additionally, there needs to be much greater investment in civil society advocacy campaigns in Brazil and other parts of South America to expand the success of the Cattle Moratorium and counteract the political pressure on forests. The private sector is directly responsible for forest destruction, and the private sector can stop it, even when governments aren’t doing their jobs.Bolivia is in dire straits – because of the same drivers as Brazil[vc_separator sep_color=”color-205066″ icon_position=”left” el_width=”20%” el_height=”4″]The new mapping data reveals that other soy-producing countries are also losing tropical primary rainforest in 2018 at a rapid clip – proving that problems lie with the broader soy industry, not just the individual governments. Brazil had the most forest loss of any country in the world, according to WRI’s data; Bolivia came in at #5 worldwide with 154,488 hectares destroyed. As in Brazil, it’s vital for the soy industry to acknowledge what is happening in Bolivia, Argentina, and Paraguay – and to act fast where local authorities fail to do so.Indonesia shows progress – but a dark ‘leakage market’ remains[vc_separator sep_color=”color-205066″ icon_position=”left” el_width=”20%” el_height=”4″]One of the most remarkable findings of the data is that Indonesia’s rate of destruction of primary forests has declined, dropping to its lowest level since 2003. There’s still way too much avoidable deforestation happening in the country, and a lot of damage that needs to be repaired, including from fires in 2015 that burned more than six million acres, led to the premature death of 100,000 people, and cost Indonesia at least USD 16.1 billion (almost 2 percent of GDP and roughly twice what the tsunami cost).

Analysis hasn’t teased out what is behind this macro-level decline in deforestation. However, it aligns with the results that Mighty Earth has seen in our work on the private sector. More than 90 percent of globally traded palm oil, the biggest historical driver of deforestation in Indonesia, is now covered by strong forest, peatland, and human rights policies – so-called No Deforestation, No Peatland development, No Exploitation (NDPE) policies.

Meanwhile, Mighty Earth and our allies have been able to bring increasing pressure on companies like Korindo, Posco Daewoo, and the Hayel Saeed Anam Group to stop deforestation in forest frontiers like Papua and Heart of Borneo. Our Rapid Response project is driving palm oil traders to respond much faster to instances of deforestation so that it’s stopped at the 100 acre level before it rises to 10,000 acres. Indeed, over the 18 months of our Rapid Response project, the worst deforester we found, Metro Lestari Jaya, cleared 17,944 acres of forest; the 10 worst cleared more than 70,000 acres combined. While that represents a lot of deforestation, it’s a substantial drop from the 750,000 acres in annual clearance for palm oil we were seeing just a few years ago.

We need to keep up this pressure. We still face rogue actors who refuse to comply with company sustainability policies and instead feed the palm oil “leakage markets” in Asia, the Middle East, and within Indonesia itself – where there is weaker consumer demand for sustainability – and in the growing but opaque biofuel market. Over the long-term, we can’t rely on the mercies of the tycoons who control the palm oil industry alone to save our forests. Governments need to act too. The Indonesian government has announced some great-on-paper policies in recent years, including a ban on new palm oil concessions and a moratorium on deforestation. However, enforcement has been sketchy, with areas targeted for deforestation by rogue palm oil companies often excised at their request. Indonesia is also building a major trans-Papua highway that risks opening up vast new areas of pristine forests to palm oil, rubber, timber, and mining industries. Indonesia’s success in reducing deforestation rests on preserving Papua’s intact forest landscapes, which comprise the third largest rainforest in the world.

The private sector momentum represents a huge opportunity for government. Companies want to sell Indonesian products on the global market, but even reduced levels of deforestation are enough to sully a brand’s reputation. If Indonesia’s government matches its action with the private sector, it can not only protect its natural resources and people, but also help drive economic growth.Chocolate industry is failing[vc_separator sep_color=”color-205066″ icon_position=”left” el_width=”20%” el_height=”4″]Even as the palm oil industry is showing signs of progress, one industry that has mastered the PR of protecting forests is clearly failing at actually protecting them: the chocolate industry.

In the countries where they operate, chocolate brands like Mars, Ferrero and Cadbury have had probably more of a devastating impact than any other forest commodity. For decades, approximately 30 percent of the cocoa coming from Côte d’Ivoire, the world’s leading cocoa producer, came from inside national parks and other protected areas. Cocoa has been the number one cause of deforestation that has destroyed 90 percent of the country’s forest cover and driven similarly severe impacts in neighboring Ghana.

In the countries where they operate, chocolate brands like Mars, Ferrero and Cadbury have had probably more of a devastating impact than any other forest commodity. For decades, approximately 30 percent of the cocoa coming from Côte d’Ivoire, the world’s leading cocoa producer, came from inside national parks and other protected areas. Cocoa has been the number one cause of deforestation that has destroyed 90 percent of the country’s forest cover and driven similarly severe impacts in neighboring Ghana.

After decades of inaction, in November 2017 the chocolate industry was finally poised to do something about deforestation. Almost all of the world’s leading chocolate and cocoa companies, as well as the governments of Côte d’Ivoire and Ghana, launched the Cocoa & Forests Initiative, pledging to immediately halt deforestation, rebuild protected areas, and restore forests. Mighty Earth celebrated these commitments at the time but noted that they needed to be implemented to make a difference.

We must now ask if these companies and their trade association, the World Cocoa Foundation, were playing a cruel joke on customers who desperately wanted to not feel guilty about indulging in a chocolate bar. WRI’s 2018 satellite data found that instead of going down in the two priority countries, “Ghana and Côte d’Ivoire experienced the highest percent rise in primary forest loss between 2017 and 2018 of any tropical country (60 percent and 26 percent, respectively).”

Thus, while Brazil tops the chart for sheer volume of forest loss, Ghana is the worst country worldwide for intensification of deforestation and Côte d’Ivoire is second worst.

This finding comports with our own recent Beyond the Wrapper report: in the protected areas in Côte d’Ivoire that we analyzed, deforestation increased in as many places as it decreased, hardly a sign that the chocolate companies were doing anything more than greenwashing. At the same time, TV exposés by French and Swiss television that found a major cocoa trader connected to ongoing deforestation inside protected areas. Our recent Easter Scorecard clearly ranks and grades the chocolate industry, showing which companies are dragging everyone else down.

It’s not surprising: the Cocoa & Forests Initiative has spent more time on diplomacy and PR instead of the number one task at hand: establishing a serious industry-wide forest monitoring and enforcement mechanism to ensure that forests are actually protected. One reason this hasn’t happened is that, so far, the Cocoa & Forests Initiative has not included tough advocacy NGOs like Mighty Earth or Greenpeace in their processes, perhaps in hopes that they wouldn’t be forced to deliver results. That’s what they’ve done for decades in promising to stop child labor in the cocoa industry, a problem that continues at a heartbreaking scale: 2.1 million kids are working in cocoa today, while average income for cocoa farmers in Ghana and Côte d’Ivoire continue at less than one dollar a day.

If the chocolate industry wants to actually see results, they need to demand that their industry association — the WCF and the coordinating partner IDH — get a robust monitoring mechanism operational before the end of this year.More countries matter: deforestation shifted from Brazil and Indonesia to a much larger group of countries[vc_separator sep_color=”color-205066″ icon_position=”left” el_width=”20%” el_height=”4″]“In 2002, just two countries—Brazil and Indonesia—made up 71 percent of tropical primary forest loss. More recent data shows that the frontiers of primary forest loss are starting to shift. Brazil and Indonesia only accounted for 46 percent of primary rainforest loss in 2018, while countries like Colombia, Côte d’Ivoire, Ghana and Democratic Republic of the Congo saw loss rates rise considerably.”

WRI’s new report shows that NGOs, funders, and the private sector need to expand their scope further beyond just the Big Two – as important as they are. For instance, Mighty Earth, Rainforest Foundation Norway, and other groups have been trying for years to support local civil society groups in efforts to protect the forests and carbon-rich peatlands of Sarawak and Sabah in Malaysian Borneo. However, because these areas fall on the Malaysian side of the border, they haven’t been eligible for the kind of funding that’s available for protecting Indonesian Borneo. And yet the data shows that primary forest clearance in Malaysia in 2018 was 42% of the amount of Indonesia.

Similarly, Paraguay, Argentina, and Bolivia haven’t been a priority even though civil society and government officials alike want help to protect their highly biodiverse forests, and they remain major sources of non-Brazilian deforestation for soy and beef. Meanwhile, data released by WRI in 2015 identified the Mekong region as one of “5 surprising hotspots for tree cover loss,” noting that “tree cover loss in Mekong countries from 2001-2014 increased by more than five times the rate of the rest of the tropics.” Cambodia had the fastest acceleration of tree cover loss in the world. Academic research published at the time showed a correlation between rubber prices and deforestation in the region – as rubber became more profitable, more trees were cleared.

These examples show that donors need to take a wider perspective on where deforestation is happening. Indeed, where funders have broadened their view before, they are getting results. The 2015 WRI report helped convince us to launch an initiative to eliminate deforestation driven by the tire and rubber industry, with the support of the Norwegian Climate and Forest Initiative, and the Arcus Foundation. This year, we joined the tire, auto, and natural rubber industries to launch the Global Platform for Sustainable Natural Rubber, which is charged with monitoring and ending deforestation for rubber. There’s a lot of work to do over the coming months to set up an effective system, but the rubber industry is off to a good start. And, to their credit, the industry is including a wide range of NGOs in its governance mechanism – suggesting that they want to avoid the pitfalls of the chocolate industry.[vc_separator sep_color=”color-205066″ icon_position=”left” el_width=”20%” el_height=”4″]WRI’s data has helped drive home the immense scale of deforestation. But despite the size of the problem, there are clear successes in the works and much more to accomplish. The data published in this year’s report will help inform our future efforts and provides valuable insight as the fight continues.